Visit the office of Gina Gibson, professor of digital communication at Black Hills

State University, and you’ll be greeted by a giant, four-foot-wide acrylic hand. Gibson

produced the hand, an art piece titled “Touch,” while serving as the first artist-in-residence

at the Sanford Underground Research Facility (SURF), a laboratory in Lead, South Dakota,

located nearly a mile underground. The surface of the hand is covered with high-resolution

scans of laboratory cables that Gibson repurposed. The result is a series of colorful

spirals that resemble the night sky as seen through the eyes of an imaginative child.

The hand is unusual office decor, but it’s a typical piece for Gibson. She takes subjects

that are normally confined to doctoral dissertations—gravitational waves, dark matter—and

filters them through her own eclectic style, often in consultation with the physicists

at those subjects’ forefront. It was that same fascination with science that prompted

Gibson to work at SURF, and more recently to spend her sabbatical in Switzerland,

serving as a visiting professor and the first artist-in-residence at the University

of Zürich Physics Institute and a Senior Fellow at the Collegium Helveticum, Swiss

Institute for Advanced Study.

Gibson’s artistic interest in physics began in 2013. That year, a South Dakota artist,

Chris Francis, started a Facebook page to create support for a hypothetical gallery at SURF.

The page caught the attention of Bill Harlan, the Lab’s communication director, who

reached out to Francis and began the process of making this a reality. Gibson was

one of the 22 artists who created art for the exhibition.

“I’d been thinking about how I enjoyed making work about something that was complicated,

so dark matter was a very fun brain puzzle,” she said. “And I started looking at residency

programs like CERN [The European Organization for Nuclear Research] and Fermi Lab

because I thought that it would be so good to make work about science. At this point,

I had been department chair and had various experiences and just really wanted to

find my way back to my creative work.”

That opportunity finally came in 2019. SURF had never previously hosted an artist-in-residence,

but the laboratory--which is nearly a mile underground because the rock reduces disruptive

cosmic radiation--was happy to make Gibson their first. Her goal was to create a body

of work that would go on display in 2020. “But you can imagine how that story goes,”

Gibson said with a laugh. “It eventually came together. And in many ways better than

expected. And it has just kept expanding.”

While at SURF as the artist-in-residence, Gibson met Dr. Björn Penning, a principal

investigator for the LUX-ZEPLIN Dark Matter Detector, and at that time a professor

at Brandeis University, though he would later take professorships at the University

of Michigan and the University of Zürich.

Gibson and Penning hit it off, having mutual respect for each other’s disciplines.

Penning suggested that the two of them do a “science art show” about SURF and the

LUX-ZEPLIN dark matter detector. Penning helped bring her exhibit to the University

of Michigan Museum of Natural History, where it was displayed until 2024. At Penning’s

invitation, Gibson traveled to Zürich that year to install the exhibit, and then again,

this year so she could repeat in Switzerland the process she mastered at SURF.

Zürich is clean, quiet, and organized, Gibson said. But her focus was on her art.

“I was very serious about the work,” she said. She went to the University of Zürich

campus each day armed with a laptop and a flatbed scanner to digitize objects. There,

she watched scientists work on experiments, got primers from leading cosmologists,

and visited some of the best physics labs on the planet. “How do you even describe

a trip to CERN, Gran Sasso or Virgo?” she gushed, referring to, respectively, the

Laboratori Nazionali del Gran Sasso and the Virgo interferometer, which are both located

in Italy.

One of the physicists’ goals was to detect dark matter, the elusive substance that

they believe makes up 27% of the universe. Gibson had her own search—she needed pieces

for her upcoming exhibit. While the scientists decided which metals the dark-matter

detector should be made from, Gibson considered which metals would compose her artwork.

(One she settled on was copper.) Her curiosity led her to go so far as digging through

discarded scientific equipment, much of which will be used for her artwork.

Residencies like Gibson’s are ultimately a search for inspiration, a substance as

elusive as dark matter. But they’re also a crucial tool to benefit professors and

students. For Gibson, spending three and a half months learning from world-class physicists

without having a degree in the field demanded of her the same intellectual courage

as her students, who are often inexperienced artists. “I didn’t always know what was

going on,” she said. “I think that was good. I had this moment of vulnerability. In

many ways, I was a student again. And I’ll bring that back to the classroom.”

Gibson’s new exhibit is set to open sometime next year.

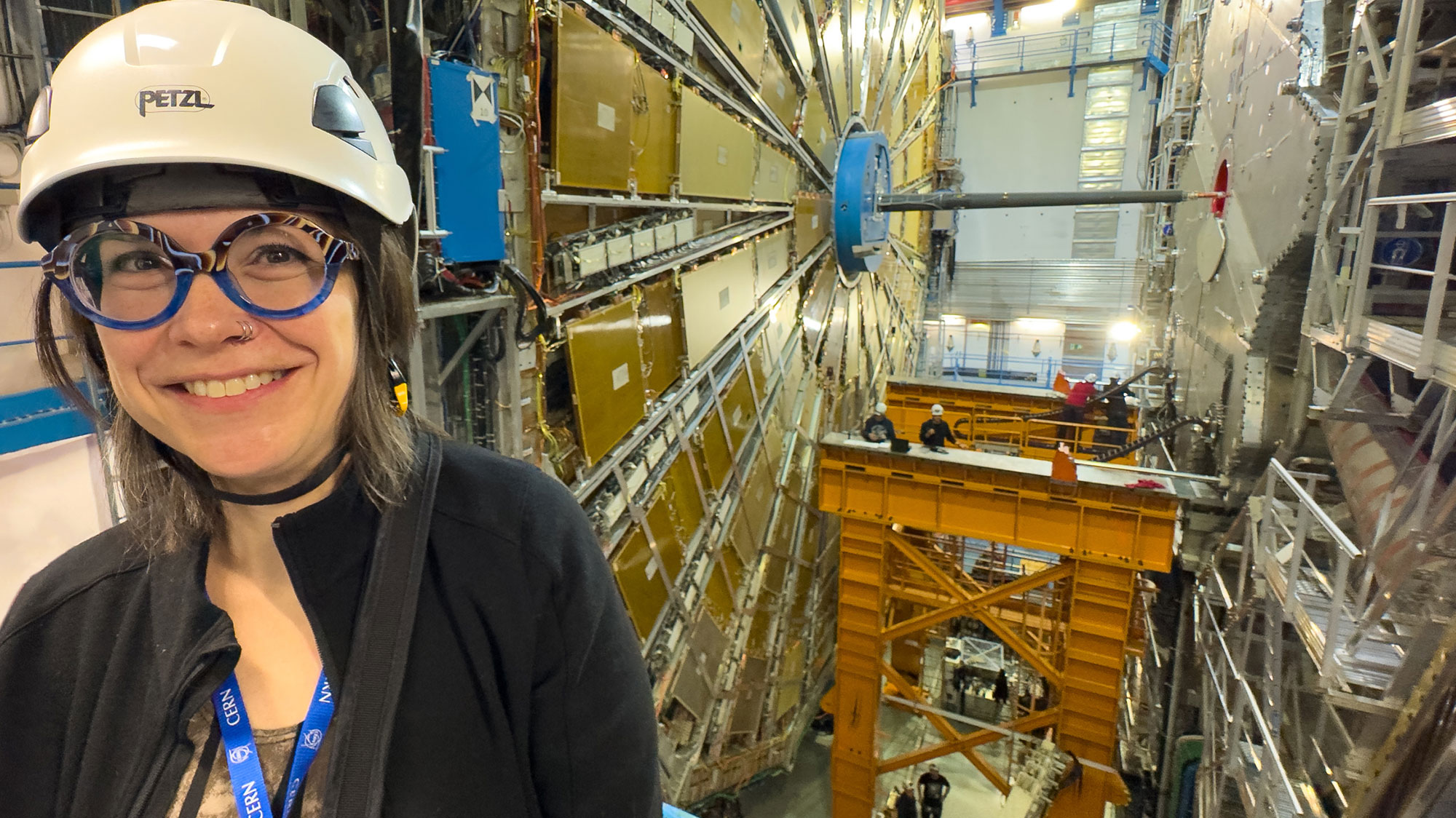

Gina Gibson stands behind the Atlas Experiment at CERN. Credit: Matt Kapust

Gina Gibson stands behind the Atlas Experiment at CERN. Credit: Matt Kapust  Gina Gibson Wears Protective Gear at Virgo Laboratory in Italy. Credit: Gina Gibson.

Gina Gibson Wears Protective Gear at Virgo Laboratory in Italy. Credit: Gina Gibson. Gina Gibson crouches to photograph a plant at Bedretto Laboratory, Italy. Credit:

Matt Kapust

Gina Gibson crouches to photograph a plant at Bedretto Laboratory, Italy. Credit:

Matt Kapust