The A. D. Humbert Collection of Clay Tablets is on display in the lower level of the

E. Y. Berry Library-Learning Center.

In the fertile valley between the Tigris and the Euphrates Rivers, the people of Sumer

and Akkad were among the first to develop organized governments for their cities [ca.

4000 B.C.].

Before 3000 B.C., the Sumerians had invented a script which was impressed into their

clay writing material with the sharp edge of a wooden stylus. Thus the symbol had

a three-dimensional, wedge-shaped look, and was called “cuneiform.” Originally, the

symbols were pictorial. However, by 2700 B.C., picture had given way to phonograms

- a symbol representing a syllable; the outward form of the symbol was simplified,

and it assumed a stylized appearance.

With the development of cuneiform, texts of all types could be preserved. It became

the writing system all over the Near East. Although clay remained the principal writing

material, cuneiform scripts have been found painted on walls of buildings, hammered

into metals, etc.

Clay tablets were usually unfired and very fragile. Once they have been baked they

are practically indestructible.

About 1950 B.C., Sumer and Akkad became a part of Babylonia. The area became known

as Mesopotamia about 331 B.C.

The fifteen original tablets were selected by Edgar J. Banks to illustrate different

types and different periods. They had been obtained by Mr. Banks directly from the

Arabs who found them at various sites in the Tigris-Euphrates Valley. The brief description

that follows includes Mr. Banks´ tablet number, the place the tablet was found, the

date of the tablet, and an explanation of the content.

In 1928, Mr. Banks apparently sold the tablets to A.D. Humbert of Spearfish Normal

School. Subsequently, Mr. Humbert donated the tablets to the Library.

In the early 1970s, the tablets were rediscovered in the Library, together with minimal

documentation. After photographing, and some preliminary research, the tablets were

taken to the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago where they were cleaned,

baked or rebaked, transliterated and/or translated, and authenticated. Upon being

returned to the Library, an appropriate showcase was designed, as well as stands for

the individual tablets, to allow them to be viewed from all sides.

The casts of the tablets, and forms used in making the casts, were donated by the

Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

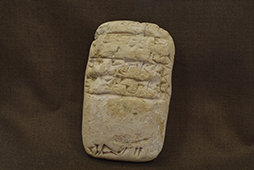

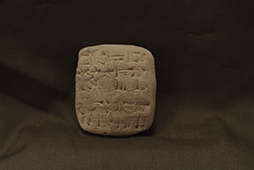

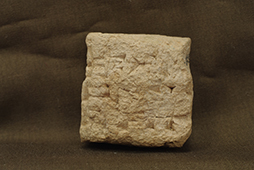

1. Kish. Old-Akkadian Period [ca. 3500 B.C.]. Issue of barley to ten persons. The

writing is very primitive on this tablet -- almost pictorial.

1. Kish. Old-Akkadian Period [ca. 3500 B.C.]. Issue of barley to ten persons. The

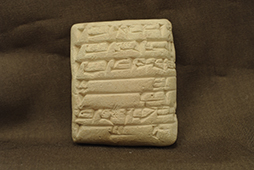

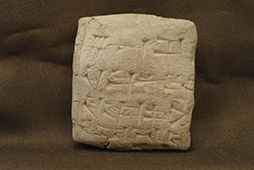

writing is very primitive on this tablet -- almost pictorial. 2. Drehem. Amar-Sin 1 [ca. 2400 B.C.]. Receipt of animals. On one edge is the numeral

22, the total number of animals.

2. Drehem. Amar-Sin 1 [ca. 2400 B.C.]. Receipt of animals. On one edge is the numeral

22, the total number of animals. 3. Drehem (near Nippur), where there was a receiving station for the temple of Bel.

Amar-Sin 5/VIII [ca. 2350 B.C.]. Receipt of animals (5 lambs, 4 sheep and 1 wild she

goat).

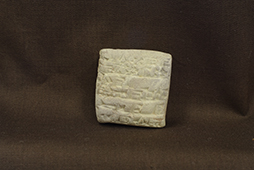

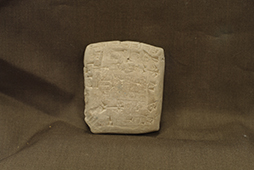

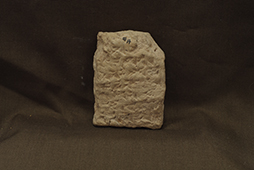

3. Drehem (near Nippur), where there was a receiving station for the temple of Bel.

Amar-Sin 5/VIII [ca. 2350 B.C.]. Receipt of animals (5 lambs, 4 sheep and 1 wild she

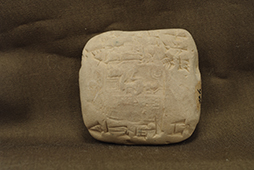

goat). 4. Jokha. Amar-Sin 6/IX [ca. 2400 B.C.]. Withdrawing of animals. A total of six sheep

withdrawn for sacrifice to various deities.

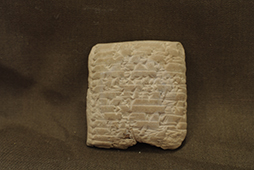

4. Jokha. Amar-Sin 6/IX [ca. 2400 B.C.]. Withdrawing of animals. A total of six sheep

withdrawn for sacrifice to various deities. 5. Drehem. Sulgi 45/XIII [ca. 2350 B.C.]. Receipt of dead animals. One ewe and one

lamb delivered on the 9th day of the month, probably for sale at the market.

5. Drehem. Sulgi 45/XIII [ca. 2350 B.C.]. Receipt of dead animals. One ewe and one

lamb delivered on the 9th day of the month, probably for sale at the market. 6. Jokha (ruin of the ancient city of Umma). Sulgi 44/I [ca. 2400 B.C.]. Receipt of

beer. Note the seal imperssion which bears the name of the scribe, Umani, and includes

the seated figure of the Moon-god, Sin, who was the chief deity of Ur. [After a tablet

was written, and while the clay was wet, the scribe rolled his cylindrical stone seal

over the tablet, thus making it impossible to change the record].

6. Jokha (ruin of the ancient city of Umma). Sulgi 44/I [ca. 2400 B.C.]. Receipt of

beer. Note the seal imperssion which bears the name of the scribe, Umani, and includes

the seated figure of the Moon-god, Sin, who was the chief deity of Ur. [After a tablet

was written, and while the clay was wet, the scribe rolled his cylindrical stone seal

over the tablet, thus making it impossible to change the record]. 7. Jokha. Su-Sin 5/XI [ca. 2350 B.C.]. Withdrawing of bread. The seal impression bears

the figure of the Moon-god.

7. Jokha. Su-Sin 5/XI [ca. 2350 B.C.]. Withdrawing of bread. The seal impression bears

the figure of the Moon-god. 8. Drehem. Su-Sin 9/III [ca. 2350 B.C.]. Receipt of kasu-plant. Includes the seal

of Lukalla.

8. Drehem. Su-Sin 9/III [ca. 2350 B.C.]. Receipt of kasu-plant. Includes the seal

of Lukalla. 9. Jokha. Su-Sin 5/IX [ca. 2400 B.C.]. Receipt of barley. Barley withdrawn for sowing,

feeding the oxen, and for the wages of hired men. The seal of Irmu.

9. Jokha. Su-Sin 5/IX [ca. 2400 B.C.]. Receipt of barley. Barley withdrawn for sowing,

feeding the oxen, and for the wages of hired men. The seal of Irmu. 10. Jokha. Ur III [ca. 2300 B.C.]. Distribution of beer and bread. This messenger

tablet exhibits a very fine cuneiform script. Unfortunately the reverse is almost

completely destroyed.

10. Jokha. Ur III [ca. 2300 B.C.]. Distribution of beer and bread. This messenger

tablet exhibits a very fine cuneiform script. Unfortunately the reverse is almost

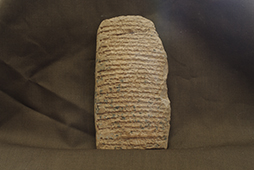

completely destroyed. 11. Tello (ruin of city of Lagas). Gudea [ca. 2200 B.C.]. Votive cone. The text reads

“For Ningirsu, the powerful warrior of Enlil, Gudea, ruler of Lagas, has accomplished

a proper thing, his (temple) E-ninnu-anzu-birbir has built and restored to its place.”

11. Tello (ruin of city of Lagas). Gudea [ca. 2200 B.C.]. Votive cone. The text reads

“For Ningirsu, the powerful warrior of Enlil, Gudea, ruler of Lagas, has accomplished

a proper thing, his (temple) E-ninnu-anzu-birbir has built and restored to its place.” 12. Tello. Sulgi 46/IX [ca. 2200 B.C.]. Receipt of grain. This is an envelope tablet.

The envelope is sealed, the tablet probably is not. The envelope can be opened only

by breaking it away.

12. Tello. Sulgi 46/IX [ca. 2200 B.C.]. Receipt of grain. This is an envelope tablet.

The envelope is sealed, the tablet probably is not. The envelope can be opened only

by breaking it away. 13. Warka (the ruin of the Biblical city of Erech of Genesis 10:10). Old Babylonian

[ca. 2000 B.C.]. Expenditure of flour for food rations of house slaves. This is a

good illustration of the business documents used by the people at the time of Abraham,

a contemporary of Hammurabi, King of Babylonia.

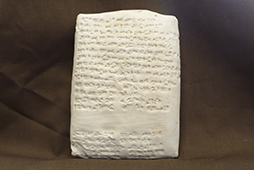

13. Warka (the ruin of the Biblical city of Erech of Genesis 10:10). Old Babylonian

[ca. 2000 B.C.]. Expenditure of flour for food rations of house slaves. This is a

good illustration of the business documents used by the people at the time of Abraham,

a contemporary of Hammurabi, King of Babylonia. 14. Warka. Ammiditana 1 [ca. 2000 B.C.]. Old Babylonian legal text.

14. Warka. Ammiditana 1 [ca. 2000 B.C.]. Old Babylonian legal text. 15. Babylon. Nebuchadnezzar year 20, month 9, day 10 [i.e., September 10, 585 B.C.].

Neo-Babylonian administrative text, recording expenditures of small amounts of silver

for oil and beer for workmen.

15. Babylon. Nebuchadnezzar year 20, month 9, day 10 [i.e., September 10, 585 B.C.].

Neo-Babylonian administrative text, recording expenditures of small amounts of silver

for oil and beer for workmen. 16. Cast of tablet found at Nippur in 1973. It concerns trading mules with enarby

Elam, today in Western Iran. Dated ca. 700 B.C.

16. Cast of tablet found at Nippur in 1973. It concerns trading mules with enarby

Elam, today in Western Iran. Dated ca. 700 B.C. 17. Cast of tablet fragmentation found on the surface of Nippur in 1973. It bears

part of a catalog of incantations against evil demons, and is dated about 600 B.C.

17. Cast of tablet fragmentation found on the surface of Nippur in 1973. It bears

part of a catalog of incantations against evil demons, and is dated about 600 B.C. 18. Contract for exchange of houses [ca. 1400 B.C.]

18. Contract for exchange of houses [ca. 1400 B.C.] Partial form used in making cast of tablet

Partial form used in making cast of tablet